Page Contents

Gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the stomach and intestines caused by viruses, bacteria, or parasites. In older adults, the condition is more dangerous because of weaker immunity, multiple chronic illnesses, and higher risk of dehydration. In a nursing home, where residents share living spaces, bathrooms, and caregivers, one infection can quickly spread to many.

Prevalence

Gastroenteritis outbreaks are common worldwide, but their impact is more severe in long-term care facilities.

Developed countries report frequent viral gastroenteritis outbreaks, especially norovirus, in nursing homes and hospitals.

Countries with tropical climates, including parts of Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America, face higher incidence of bacterial and parasitic gastroenteritis because warm, humid weather supports pathogen survival.

In Singapore, norovirus and rotavirus are often the leading causes, while bacterial cases linked to contaminated food or water also occur.

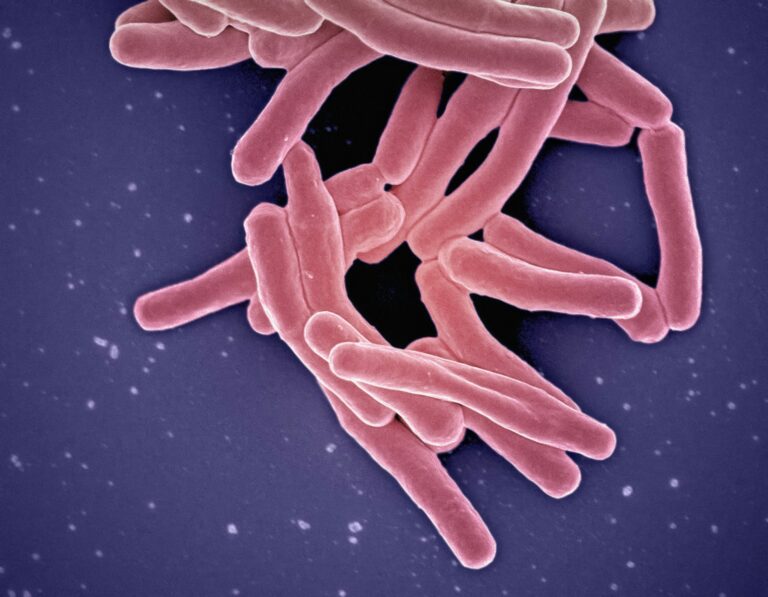

3 types of pathogens

Gastroenteritis in nursing homes can be caused by:

Viruses – Norovirus (most common in outbreaks), rotavirus, adenovirus.

Bacteria – Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Clostridium perfringens, Campylobacter.

- Parasites – Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium.

Each pathogen spreads differently, but all thrive in environments with close contact, poor hygiene, and contaminated food or water.

Sources of infection and outbreak triggers

Pathogens enter the body through ingestion of contaminated food, water, or hands. In nursing homes, outbreaks often start from:

Improper food handling or undercooked food.

Contaminated water supply.

Unwashed hands of staff or residents after toileting.

Shared equipment, such as commodes or bedpans, not disinfected properly.

Once one resident is infected, vomiting and diarrhea contaminate surfaces and hands, enabling rapid spread through person-to-person contact.

Stages of gastroenteritis infection

Incubation

Pathogen enters the body, no symptoms at first. This can range from hours (norovirus) to several days (Giardia).Acute illness

Sudden onset of diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal cramps.Recovery

Usually within 2–7 days, but elderly residents may experience prolonged weakness and appetite loss.Post-infection risks

Some bacteria (e.g., E. coli O157:H7) can cause kidney damage, while dehydration can lead to hospitalisation.

Signs, symptoms, and complications

Common signs: Watery diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, fever, abdominal cramps, fatigue.

Complications in elderly: Severe dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, kidney injury, worsening of chronic diseases, sepsis in bacterial infections.

High-risk residents: Those with dementia (unable to report symptoms), those on diuretics, and frail residents with poor oral intake.

Infection control plan to manage gastroenteritis

The chain of infection has six links. Breaking any one link stops the outbreak from spreading. In a nursing home, all six must be addressed at the same time.

Infectious agent

Identify the causative organism quickly through stool tests and clinical reports.

For suspected viral gastroenteritis (e.g., norovirus), assume high transmissibility even before results return.

Notify local public health authorities early for guidance and surveillance support.

Reservoir

Infected residents are the main reservoir, but staff and contaminated surfaces can also harbour pathogens.

Isolate residents with gastroenteritis symptoms in designated rooms or cohort them in one area with dedicated staff with full PPE.

Staff with diarrhea or vomiting must not work until at least 48 hours after symptoms stop.

Clean and disinfect toilets, commodes, and shared bathrooms after every use.

Portal of exit

Vomit and diarrhea carry the highest pathogen load.

Staff must wear full PPE (gloves, masks, gowns, and eye protection) when handling waste.

Contain soiled linens in sealed laundry bags and wash at high temperature.

Cover coughs and sneezes, and dispose of tissues immediately in lined bins.

Mode of transmission

The main transmission routes are person-to-person contact, contaminated hands, and environmental surfaces.

Enforce strict handwashing with soap and water, as alcohol rubs are less effective against norovirus.

Use chlorine-based disinfectants (1000–5000 ppm) on high-touch surfaces like bed rails, tables, and toilet handles.

Stop communal dining, group therapy, and recreational activities until the outbreak is contained.

Dedicate equipment such as thermometers, blood pressure machines, and commodes to infected residents.

Portal of entry

Pathogens usually enter through the mouth when residents touch contaminated hands, food, or utensils.

Provide meals on disposable trays or ensure utensils are disinfected properly.

Reinforce glove and gown use when cleaning residents or handling bodily fluids.

Educate staff to avoid touching their face while working and to perform hand hygiene before eating.

Susceptible host

Elderly residents with chronic illness, frailty, or poor fluid intake are most vulnerable.

Start oral rehydration early, and escalate to IV fluids for those unable to drink.

Monitor vital signs, urine output, and electrolytes closely.

Provide education to residents, families, and staff on early reporting of symptoms.

Ensure staff are trained in outbreak protocols and emergency escalation.

By disrupting the chain of infection, nursing homes create multiple barriers that block the spread of gastroenteritis. Outbreaks are shorter, less severe, and far fewer residents require hospital transfer.

Conclusion

Gastroenteritis outbreaks in nursing homes can escalate quickly and cause serious complications in elderly residents.

Understanding the sources, signs, and stages of infection, and applying the chain of infection model, helps facilities respond swiftly and effectively. Speed in detection, strict hygiene, staff training, and clear outbreak protocols are the cornerstones of protecting vulnerable residents.